Saturday, September 30, 2006

What a Life!

Over at the Telegraph, John Gibbens drops in on my old haunt, Booth's in Hay on Wye:

Yup. That sounds about right.

What he does find in Hay, though, is a book (The Second Post) by the very prolific E.V. Lucas, whose work I only just discovered earlier this year in much the same way -- in my case, by picking up an old copy of Lucas on Charing Cross.

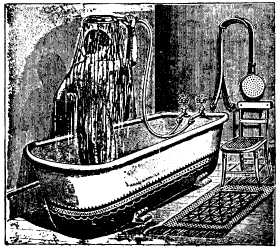

Though out of print now, Lucas and George Morrow laid the groundwork for Donald Barthelme, Terry Gilliam, and innumerable others with their 1911 "autobiography" What a Life!, which cut and paste department store catalogue illustrations around an absurd narrative. The book is now online:

The eccentric Sir William Goosepelt was a friend of mine. Among his other odd ways he often indulged in the luxury of a treacle bath.

Sir William's ears were so large that he required a chin-strap to keep his hat on. From this circumstance he earned an unenviable reputation for impoliteness towards ladies.

Could one succumb to an overdose of second-hand books, like a king to a surfeit of lampreys? I hadn't thought so until I visited Booth's in Hay-on-Wye, the self-proclaimed World's Biggest Second-hand Bookshop. The wilderness of shelves receding into twilight, the sheer mass of volumes, staggered my brain; the air of ageing paper caught in my throat, and I fled, back into the streets of this little village that is a bibliopolar metropolis.

Yup. That sounds about right.

What he does find in Hay, though, is a book (The Second Post) by the very prolific E.V. Lucas, whose work I only just discovered earlier this year in much the same way -- in my case, by picking up an old copy of Lucas on Charing Cross.

Though out of print now, Lucas and George Morrow laid the groundwork for Donald Barthelme, Terry Gilliam, and innumerable others with their 1911 "autobiography" What a Life!, which cut and paste department store catalogue illustrations around an absurd narrative. The book is now online:

The eccentric Sir William Goosepelt was a friend of mine. Among his other odd ways he often indulged in the luxury of a treacle bath.

Sir William's ears were so large that he required a chin-strap to keep his hat on. From this circumstance he earned an unenviable reputation for impoliteness towards ladies.

Borat's Glorious Ancestor

Loyal readers will remember Alex MacBride: he was the UCLA linguistics grad student who, after seeing our hardcover edition of English as She is Spoke, contacted me with the first really convincing theory of how the disaster that is English came about. In a nutshell: Pedro Carolino probably hijacked Da Fonseca's perfectly decent Portuguese to French phrasebook and ran it ineptly through a French/English dictionary.

I just heard from Alex this week -- he's now a linguist at Google -- and he sends great news. Namely, Google's book digitizing project now has the original 1855 edition online.

Makes happy is! Make for you to run fasts to seeing excelling book!

I just heard from Alex this week -- he's now a linguist at Google -- and he sends great news. Namely, Google's book digitizing project now has the original 1855 edition online.

Makes happy is! Make for you to run fasts to seeing excelling book!

Sunday, September 24, 2006

Japanese As She Is Spoke

Looks like The Scotsman is the first out the gate -- or the only one turning up on a Google News search, at least -- to review the English edition of Train Man, a book that has been a phenomenon in Japan.

Sounds interesting enough. But, the review notes, it might be sunk by what sounds like an overly literal translation: "Idiomatic Japanese phrases are translated into a disjointed quasi-English: "This blow opened up the floodgates connected to the Geek's tearducts which had long been arid as the land on Mars."

Uh-oh.

"So far," they note, "Train Man has been translated into five manga comics, a film, a theatre play, a guidebook and a two-hour television special dramatising the story."

It has its roots in 2004, when an anonymous internet user posted a message on a popular Japanese board to describe a fracas on a subway. He had been sitting next to a beautiful woman on the train when a drunk entered the car and began hassling the passengers. When he began to badger the woman, the internet poster told the drunk off and became involved in a brief struggle before the police were called. In the excited chatter on the board, the poster soon received the nickname "Densha Otoko" (Train Man).

Later, Train Man posted to tell his fellow netizens that he was astonished to receive a gift from the young woman to thank him for his bravery; two cups and saucers made by Hermès of Paris. Egged on by his fellow geeks he arranges to meet "Hermès" and the uncertain progress of their romance is aired in front of thousands of eager computer users.

Sounds interesting enough. But, the review notes, it might be sunk by what sounds like an overly literal translation: "Idiomatic Japanese phrases are translated into a disjointed quasi-English: "This blow opened up the floodgates connected to the Geek's tearducts which had long been arid as the land on Mars."

Uh-oh.

Colbert on the MacArthur Awards

Quite possibly the funniest thing I have seen all week, and maybe all month:

Saturday, September 23, 2006

Big Doodle Bang

This week Cabinet magazine and Basic Books released Presidential Doodles, to plenty of gratifying press coverage. (Ahh, the writer's oxygen!) I wrote the book's foreword, Doodlers-In-Chief, and you can read the full text here. It was a fun project, and not least because I quickly discovered that... well, nobody had really written a history of doodling before. I had no precedent to draw upon.

So: I made my own history of doodling.

Not the least of my challenges was explaining the strange lopsidedness of the book. Namely, Cabinet's researchers were finding way more doodles from after 1850 than from before. After much head-scratching, I laid out my Grand Unified Theory of the Big Doodle Bang:

The labor of quill writing meant that an eighteenth-century meeting required a secretary to take notes: others were not expected to trouble themselves with writing, and the secretary was certainly not allowed to doodle... In fact, three things needed to happen before doodling could become, if not the Sport of Kings, at least the Fidget of Presidents. The first was the invention of the steel-nibbed pen. Like any terribly useful invention, nobody can quite agree on its origins. One of the earliest accounts places a steel pen in the hand of a certain Peregrine Williamson, a Baltimore jeweler in the first few years of the 1800s. Peregrine was terrible at cutting quills; in desperation, he contrived a sort of steel quill that would never need sharpening. He didn’t keep his jerry-rigged contraption to himself for long, though: soon, he was making $600 a month from his invention. By 1823, the Englishman James Perry was mass-producing them, and a new generation of children learned to write with the newfangled metal quill. “The Metallic pen is in the ascendant, and the glory of goosedom has departed forever,” one textbook stated flatly.

But then there’s the matter of paper. Paper was manufactured from old rags, and by the age of the steel pen, demand was outstripping the national supply of used underwear and grubby bonnets: paper was expensive, and not the sort of thing you’d waste on aimless scribbles. Everything from hay to hemp was tried out as a substitute material, with mixed results at best. It took the German inventor Friedrich Keller, in 1843, to develop the first recognizably modern process for mass-producing paper out of ground wood pulp. The resulting product was easily shipped via burgeoning rail systems. Soon, paper was abundant; it was sold by the pad, the memo book, and the sheaf.

Writing itself became looser and more doodle-like. Itinerant penmanship instructors, often juggling other fashionable sidelines in daguerreotyping and cutting silhouettes, distinguished themselves in the mid-1800s with manuals featuring ever-more baroque swirls and flourishes, not to mention fanciful drawings of angels, birds, and grinning fish; indeed, the title page of at least one textbook is so covered with this calligraphic frippery that the words themselves are obliterated. But by the time of Abraham Lincoln, a generation of children had grown up with increasingly affordable pencils and steel pens. These youngsters practiced flourishes, repeated words over and over, and sketched out fanciful beasts in cheap notebooks and on the endpapers of Latin grammars—and, just as their schoolmasters had claimed, a few would grow up to be president.

One of these was Harry Truman, and yet when Cabinet contacted his Presidential Library, they claimed Harry didn't doodle. That's funny, I told my editor Sina, because right now I'm looking at a Truman doodle in an old New York Times article.

Sleep contentedly, America: the historical record now stands corrected.

So: I made my own history of doodling.

Not the least of my challenges was explaining the strange lopsidedness of the book. Namely, Cabinet's researchers were finding way more doodles from after 1850 than from before. After much head-scratching, I laid out my Grand Unified Theory of the Big Doodle Bang:

The labor of quill writing meant that an eighteenth-century meeting required a secretary to take notes: others were not expected to trouble themselves with writing, and the secretary was certainly not allowed to doodle... In fact, three things needed to happen before doodling could become, if not the Sport of Kings, at least the Fidget of Presidents. The first was the invention of the steel-nibbed pen. Like any terribly useful invention, nobody can quite agree on its origins. One of the earliest accounts places a steel pen in the hand of a certain Peregrine Williamson, a Baltimore jeweler in the first few years of the 1800s. Peregrine was terrible at cutting quills; in desperation, he contrived a sort of steel quill that would never need sharpening. He didn’t keep his jerry-rigged contraption to himself for long, though: soon, he was making $600 a month from his invention. By 1823, the Englishman James Perry was mass-producing them, and a new generation of children learned to write with the newfangled metal quill. “The Metallic pen is in the ascendant, and the glory of goosedom has departed forever,” one textbook stated flatly.

But then there’s the matter of paper. Paper was manufactured from old rags, and by the age of the steel pen, demand was outstripping the national supply of used underwear and grubby bonnets: paper was expensive, and not the sort of thing you’d waste on aimless scribbles. Everything from hay to hemp was tried out as a substitute material, with mixed results at best. It took the German inventor Friedrich Keller, in 1843, to develop the first recognizably modern process for mass-producing paper out of ground wood pulp. The resulting product was easily shipped via burgeoning rail systems. Soon, paper was abundant; it was sold by the pad, the memo book, and the sheaf.

Writing itself became looser and more doodle-like. Itinerant penmanship instructors, often juggling other fashionable sidelines in daguerreotyping and cutting silhouettes, distinguished themselves in the mid-1800s with manuals featuring ever-more baroque swirls and flourishes, not to mention fanciful drawings of angels, birds, and grinning fish; indeed, the title page of at least one textbook is so covered with this calligraphic frippery that the words themselves are obliterated. But by the time of Abraham Lincoln, a generation of children had grown up with increasingly affordable pencils and steel pens. These youngsters practiced flourishes, repeated words over and over, and sketched out fanciful beasts in cheap notebooks and on the endpapers of Latin grammars—and, just as their schoolmasters had claimed, a few would grow up to be president.

One of these was Harry Truman, and yet when Cabinet contacted his Presidential Library, they claimed Harry didn't doodle. That's funny, I told my editor Sina, because right now I'm looking at a Truman doodle in an old New York Times article.

Sleep contentedly, America: the historical record now stands corrected.

Sunday, September 17, 2006

That's Life

Saturday, September 16, 2006

This Week in Weird-Ass Books

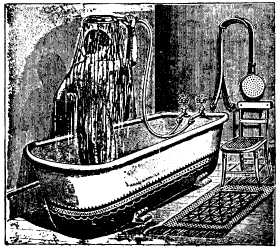

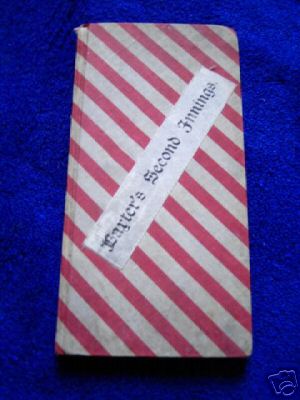

Goofy binding of the week:

Baxter's Second Innings (1892). A children's book about cricket that, naturally, resembles a... um, a peppermint stick? Sure, okay. You lick that binding. The diagonally pasted title only deepens the mystery. My guess is that they realized the labels were wider than the book after they printed them all up, and they didn't want to... well, you know, pay for another print job. Hence: diagonal titling!

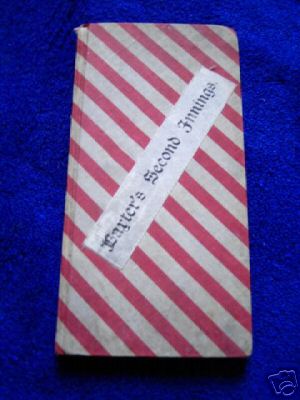

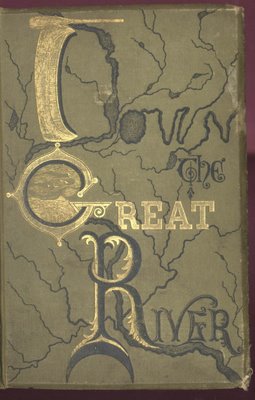

Font of the week:

The cover of Down the Great River (1888), by Capt. Willard Glazer. Isn't that just awesome? Try finding that one in Quark, smartypants.

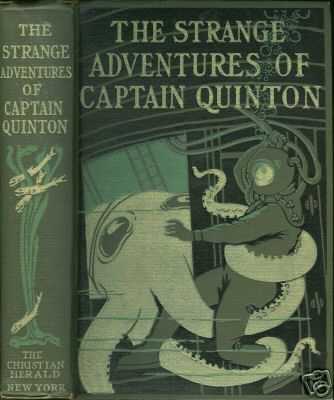

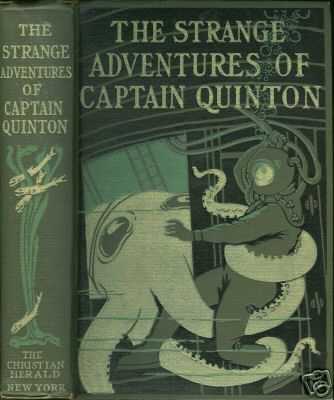

And now, a giant octopus:

Yep, it's The Strange Adventures of Captain Quinton: Being a Truthful Record of the Experiences and Escapes of Robert Quinton During His Life Among the Cannibals of the South Seas, As Set Down By Himself. I run into this book occasionally, and let me just say now that it is my favorite cover illustration and title ever.

No reason, really: it just always makes me smile.

Baxter's Second Innings (1892). A children's book about cricket that, naturally, resembles a... um, a peppermint stick? Sure, okay. You lick that binding. The diagonally pasted title only deepens the mystery. My guess is that they realized the labels were wider than the book after they printed them all up, and they didn't want to... well, you know, pay for another print job. Hence: diagonal titling!

Font of the week:

The cover of Down the Great River (1888), by Capt. Willard Glazer. Isn't that just awesome? Try finding that one in Quark, smartypants.

And now, a giant octopus:

Yep, it's The Strange Adventures of Captain Quinton: Being a Truthful Record of the Experiences and Escapes of Robert Quinton During His Life Among the Cannibals of the South Seas, As Set Down By Himself. I run into this book occasionally, and let me just say now that it is my favorite cover illustration and title ever.

No reason, really: it just always makes me smile.

Caleb Crain's blog...

Sunday, September 10, 2006

The Billion Lira Note

While talking over dinner at the festival, conversation naturally turned to... television. (Hey, I'm only human.) Apparently about 15 years ago there was an Italian game show that would give a gigantic wad of lira to the contestant -- equivalent, say, to 100,000 Euro. The one rule was that you had to spend all the money in an hour.

Anyone who has encountered Italian shop hours, or tried to get any order filled quickly there, will quickly realize why this is the most cruelly funny idea ever devised for a game show. Contestants would typically try a car dealership first, resulting in exchanges like this:

It being Italy, a wine merchant was the next logical stop:

The show's producers rarely lost their money.

This is surely the only game show to be the living embodiment of a Mark Twain story.

Anyone who has encountered Italian shop hours, or tried to get any order filled quickly there, will quickly realize why this is the most cruelly funny idea ever devised for a game show. Contestants would typically try a car dealership first, resulting in exchanges like this:

"I want to buy a car!"

"Excellent! Come by tomorrow and we'll do the paperwork."

"No, I need it now. Now!"

"Ehh..."

"I have the money in my hand! For your most expensive car! This hour! The. Money. Is. In. My. Hand!"

"Today's not so good."

It being Italy, a wine merchant was the next logical stop:

"I need 20,000 bottles! I have your money right here!"

"Ehh..."

The show's producers rarely lost their money.

This is surely the only game show to be the living embodiment of a Mark Twain story.

Saturday, September 09, 2006

Festivaletteratura

I'm just back from the Festivaletteratura, Italy's largest literary festival and what may soon become a required stop for anyone who wants to bookend their summers between the Hay festival and a trip to Italy. Like Hay, it's held in an impossibly gorgeous old town (Mantova). But because Italian bookstores are dense with translated work -- the children's author Bianca Pitzorno estimated to me that roughly 70% of their bestsellers are foreign translations -- it means that there's a very noticeable international presence among the authors there. Aside from yours truly, David Sedaris, Julia Kristeva, and Jasper Fforde were all in town for it too.

So, really: you should go next year. It's pretty awesome.

The first thing I learned in Italy: apparently most of my readers are there, and not America. Who knew? This is the first time that I have ever sold out an event, or been ambushed by photographers at the door.

The second thing I learned: even if you're not particularly fond of coffee, it is possible to become addicted to really well-made cappuccinos.

The third thing I learned: that I cannot recommend five books to anybody.

Bizarrely, in the course of 10 interviews in a row on Wednesday alone -- a guaranteed way to lose your grip on reality, incidentally -- I was asked 5 times in succession: "Name 5 books that everyone should own." The first to throw this spanner into my gears was a TV crew from RAI 1, one of the national channels. My response: to stand stunned for a moment and then say, "Turn off the camera. I need a minute."

Eventually, I gave them this response: "Everybody should have five books that they haven't seen in anybody else's house."

I thought that was that, until the next interviewer asked the same question. And the next. And the next. Finally, sitting between translator Nicola Nobili and journalist Stefano Salis at a public interview in the Giardino di casa Martinia, I was cornered by the (friendly) crowd:

At first, I responded: "I recommend books to individuals. I can't imagine recommending one book to everybody.... if someone tried that on me, I'd run in the other direction."

"Thank you for explaining this," one member of the audience said while a translator whispered simultaneously in my ear. "Now, tell us: what are the five books?"

Uh-oh.

"Ok," I sighed. "I'll give you one. Three Men in a Boat, by Jerome K Jerome. It's not edifying, and it's not morally or philosophically elevating. But it has the warmth of human presence -- and that is the highest praise I give to a book."

"Thank you," came a response. "You have four to go."

So I gave them one at a time, though they had to pry them out of me in successive questions: Dodie Smith's I Capture the Castle, Lee Meriwether's A Tramp Trip: How to See Europe on 50 Cents a Day, Religio Medici by Thomas Browne, and Burton's Anatomy of Melancholy. They were not, I explained, five books for every home, nor were they five books for for all time. They were just five books on my mind that week.

I'm not sure that I can explain my resistance to issuing a personal canon, but I'm even more bewildered by the desire for one. To, the personal search for books is at least half the point: and it is utterly dependent on whatever odd cicrumstances, moods, and places happen to converge on any given day. Moreover, my stock of books constantly shifts every time I move house. I reevaluate what each book means to me, and whether I even want to keep it around.

But in retrospect, I suppose the question was really a simpler one, and had little to do with canons at all. At least, I hope so. At its root, it is simply a variation on "Tell us about yourself."

Strangely, for a memoirist, I really have no idea how to answer that question either.

So, really: you should go next year. It's pretty awesome.

The first thing I learned in Italy: apparently most of my readers are there, and not America. Who knew? This is the first time that I have ever sold out an event, or been ambushed by photographers at the door.

The second thing I learned: even if you're not particularly fond of coffee, it is possible to become addicted to really well-made cappuccinos.

The third thing I learned: that I cannot recommend five books to anybody.

Bizarrely, in the course of 10 interviews in a row on Wednesday alone -- a guaranteed way to lose your grip on reality, incidentally -- I was asked 5 times in succession: "Name 5 books that everyone should own." The first to throw this spanner into my gears was a TV crew from RAI 1, one of the national channels. My response: to stand stunned for a moment and then say, "Turn off the camera. I need a minute."

Eventually, I gave them this response: "Everybody should have five books that they haven't seen in anybody else's house."

I thought that was that, until the next interviewer asked the same question. And the next. And the next. Finally, sitting between translator Nicola Nobili and journalist Stefano Salis at a public interview in the Giardino di casa Martinia, I was cornered by the (friendly) crowd:

At first, I responded: "I recommend books to individuals. I can't imagine recommending one book to everybody.... if someone tried that on me, I'd run in the other direction."

"Thank you for explaining this," one member of the audience said while a translator whispered simultaneously in my ear. "Now, tell us: what are the five books?"

Uh-oh.

"Ok," I sighed. "I'll give you one. Three Men in a Boat, by Jerome K Jerome. It's not edifying, and it's not morally or philosophically elevating. But it has the warmth of human presence -- and that is the highest praise I give to a book."

"Thank you," came a response. "You have four to go."

So I gave them one at a time, though they had to pry them out of me in successive questions: Dodie Smith's I Capture the Castle, Lee Meriwether's A Tramp Trip: How to See Europe on 50 Cents a Day, Religio Medici by Thomas Browne, and Burton's Anatomy of Melancholy. They were not, I explained, five books for every home, nor were they five books for for all time. They were just five books on my mind that week.

I'm not sure that I can explain my resistance to issuing a personal canon, but I'm even more bewildered by the desire for one. To, the personal search for books is at least half the point: and it is utterly dependent on whatever odd cicrumstances, moods, and places happen to converge on any given day. Moreover, my stock of books constantly shifts every time I move house. I reevaluate what each book means to me, and whether I even want to keep it around.

But in retrospect, I suppose the question was really a simpler one, and had little to do with canons at all. At least, I hope so. At its root, it is simply a variation on "Tell us about yourself."

Strangely, for a memoirist, I really have no idea how to answer that question either.

Sunday, September 03, 2006

In Praise of Fake Vomit

This week over at The Stranger, I delve into Kirk Deramarais's Life of the Party, a beautiful new visual history of the S.S. Adams Company.

Haven't heard of S.S. Adams? Well, you've certainly been squirted, buzzed, and otherwise annoyed by them:

Ah, I can't help it: I just love the idea of Henry James with a dribble glass.

One additional tidbit, which got sacrificed to the Word Count God and didn't make into the Stranger:

Cheap copies of the Johnson catalogue --both in it's original and Shepard editions -- turn up all the time on eBay, and it's an ideal coffee-table purchase. Kirk himself has a great page on 1970s Johnson Smith comic-book ads...

Haven't heard of S.S. Adams? Well, you've certainly been squirted, buzzed, and otherwise annoyed by them:

In 1904, Soren Sorenson Adams was a Danish immigrant toiling in a dye factory bedeviled by a chemical byproduct that induced violent sneezing. Voila!—sneezing powder was born, and so was the Cachoo Sneeze Powder Company. By 1906 it was the S.S. Adams Co., and a new American industry in squirt rings and exploding cigars was born. Nickel and dime wackiness flew fast and furious out of their New Jersey warehouse: 1908 heralded the spring-loaded Snake in the Jam, and the next year brought us the immortal Dribble Glass. It's comforting to imagine Henry James's grandchildren afflicting him with this crap.

Ah, I can't help it: I just love the idea of Henry James with a dribble glass.

One additional tidbit, which got sacrificed to the Word Count God and didn't make into the Stranger:

The other Adamic father of gag art was the Johnson Smith Company of Mt Clemens, Michigan; innumerable children pined for their iconic X-Ray Specs. Their 1929 catalogue was reprinted in 1970 as a facsimile edition with an introduction by Jean Shepard—a perfect pairing—and it's well worth digging up from used bookstores. Put Life Of the Party over one eye and a battered old Johnson Smith catalogue over the other, and you'll have your very own pair of x-ray specs into American childhood.

Cheap copies of the Johnson catalogue --both in it's original and Shepard editions -- turn up all the time on eBay, and it's an ideal coffee-table purchase. Kirk himself has a great page on 1970s Johnson Smith comic-book ads...

It's Been Several Days...

...and I still don't know what to say about this.

It's not actually a mystifying decision -- it's been all too clear that the Village Voice's new owners have been taking a belligerent-drunk-with-a-chainsaw approach to the staff changes. But it should be a mystifying decision. Ed Park has been, bar none, the best and most encouraging editor I've ever worked with.

I mean, where else could I cover inept stuttering novels and Victorian monkey sex-ed?

Of my only two remaining must-read alt-weekly book sections (The Stranger and The Onion A.V. Club), neither originate from NYC. Hmm.

It's not actually a mystifying decision -- it's been all too clear that the Village Voice's new owners have been taking a belligerent-drunk-with-a-chainsaw approach to the staff changes. But it should be a mystifying decision. Ed Park has been, bar none, the best and most encouraging editor I've ever worked with.

I mean, where else could I cover inept stuttering novels and Victorian monkey sex-ed?

Of my only two remaining must-read alt-weekly book sections (The Stranger and The Onion A.V. Club), neither originate from NYC. Hmm.