Sunday, July 30, 2006

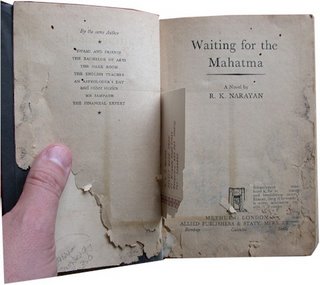

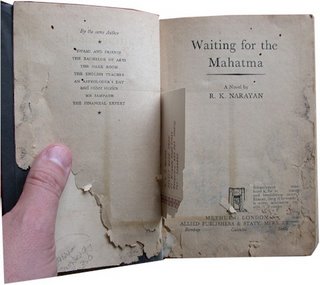

The Amazing Disintegrating Book

Scott Brown of Fine Books & Collections has been keeping a splendid antiquarian Fine Books Blog; one of my favorite posts is a classic good news/bad news combination.

Good news!... He's discovered an unrecorded first edition by R.K. Narayan.

Bad news!... It's covered in black mold....

As Scott describes it:

Good news!... He's discovered an unrecorded first edition by R.K. Narayan.

Bad news!... It's covered in black mold....

As Scott describes it:

Someone should sponsor a contest for the most shot-to-hell-and-back copy of an old book. I've got a few that would be fine contenders.The pages weren't "cut," they were disintegrating from mildew. The paper literally fell apart in my hands as I turned the pages. Black mold crept in from the edges and some pages were almost consumed by the stuff. I quickly photographed it (My wife downloaded the pictures from the camera and put them in a folder called "Scott's Funky Old Book"), put it in a Zip-Lock bag, and stuck it in the tool closet, as far from the rest of my books as possible.

Saturday, July 29, 2006

Shut Up and Read

Hey, remember how your medieval lit prof told you that people never used to read silently? Umm, never mind about that, today's Guardian reports:

Interesting....

It is a myth that the ancients only or normally read out loud - a myth we appear to want to believe, since the evidence against it is strong.... I consulted Alberto Manguel's A History of Reading (Flamingo), which was published in the same year as Gavrilov's and Burnyeat's articles. Manguel believes that the passage in Augustine is "the first definite instance [of silent reading] recorded in western literature". He is well aware of the evidence to the contrary, but he finds it unconvincing. Thus Manguel: "According to Plutarch, Alexander the Great read letter from his mother in silence in the fourth century BC, to the bewilderment of his soldiers."... But these bewildered soldiers are Manguel's importation. They have been brought into the story in order to make it seem exceptional. Manguel shamelessly fudges the argument.

Interesting....

Pot, meet Kettle...

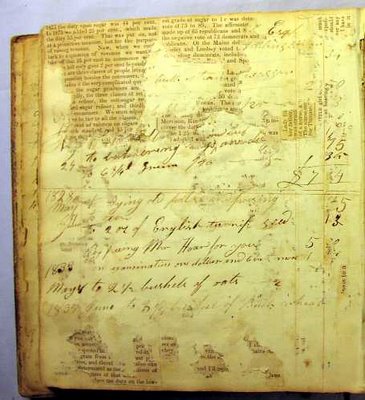

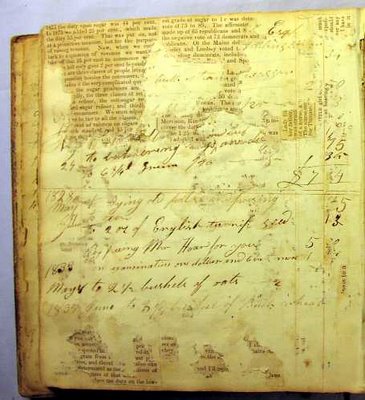

A Curious Example of Hidden Writing

A very peculiar item turned up on eBay this week: the owner of what initially looked like merely another 19th century scrapbook of newspaper clippings peeled away some newsprint and discovered a hidden journal underneath:

The seller goes on to describe it:

Update: Caleb Crain points out to me that he's come across other old account books and the like that were recycled in this penny-pinching manner: "It's almost a sure bet that the newspaper clippings that the ebay fellow was 'clearing' are of more scholarly interest than the old account book beneath..."

The seller goes on to describe it:

I decided to see if I could clear the first few pages to see if the owner's name, or scriber of the journal was present. Selecting the pages that had lo[o]se clippings I removed enough using steam and in some cases a mild warm vinegar solution with a thin artist pallet knife. My first discovery was that the beginning of the journal was kept by "The Wife of Husband Ellis Clerk." At first I thought that is was "Ellis Clark" and an internet search of the 1880 census data did find an Ellis Clark with an 1807 birth date. Only thing was it listed him as a farmer and residing in Pennsylvania at that time, which led me to believe it was not our guy as the newspaper clippings are mainly from 1880-81 New England publications. After viewing multiple entries it struck me that it may be "Clerk", and not Clark.The item didn't sell -- he asked way too much -- but it raises an interesting question. Was this a common practice? There are plenty of these old scrapbooks around; they turn up on eBay all the time. It might be worthwhile to pry up a clipping or two from them to see just what, if anything, is going on in there....

Next I cleared the inside front cover which was also covered with clippings, these came off rather easily but did not help. I then went to the first page which right in the top in large type-set print was "C DWIGHT ELLIS", as they say, never ignore the obvious. This time the 1880 census turned up a Dwight Ellis, born 1807 in Massachusetts, now age 78 at the 1880 census, no occupation listed, just "At home in Hartford, Windsor, Vermont." .... [I] continued to clear the first page, which turned out to be very rewarding, yet a little perplexing. The cleared page reveled a name in the center, Pierpoint Phillips, Montgomery, Alabama. Again the 1880 census picks Pierpoint Phillips up in Woodstock, Windham, Connecticut, age 75, and occupation as "Retired Merchant." Now if this is him, and I believe it is as he was born in Rhode Island, he was in Montgomery, Alabama sometime between 1819 and 1820. He would have then returned to the Milton and turn the book over to his trusted clerk, Dwight Ellis....

I also believe that is was Pierpoint that covered the journal, possibly to keep others from knowing his business, or maybe there are discrete transactions that bypassed tariffs, but whatever the case may, almost every square inch of the journal was covered, and many with the same newspaper pictures or stories.

Update: Caleb Crain points out to me that he's come across other old account books and the like that were recycled in this penny-pinching manner: "It's almost a sure bet that the newspaper clippings that the ebay fellow was 'clearing' are of more scholarly interest than the old account book beneath..."

Sunday, July 23, 2006

Berners' Folly

Speaking of follies, yesterday's Guardian reviews the latest issue of The Follies Journal, a yearly journal dedicated to architectural follies. It is published, naturally, by The Folly Fellowship -- an organization which I think I may have to join, if simply for the name.

Of one of the founding fathers, the Guardian writes:

The Berners mansion is still very much around. And yes, they still dye their doves:

Of one of the founding fathers, the Guardian writes:

They seem to have been inspired by... the artist, writer, composer and complete eccentric Lord Berners. Berners, who installed a clavichord in the back of his Rolls-Royce and was given to dyeing doves unnatural hues, had overcome fierce local opposition to have a tower with a "Gothic top-not" built at Farringdon, his Berkshire seat in 1935.

The Berners mansion is still very much around. And yes, they still dye their doves:

Hatful of Hollow

A good month for tinfoil-hat wearin' theories: a few weeks ago the Voice ran my review of David Standish's history Hollow Earth, and on Friday an eagle-eyed Ed Park caught this article by Umberto Eco in the International Herald Tribune. It initially looks like another Hollow Earth piece, but turns out to be... a very kind review by Eco of Banvard's Folly!

Oh, I'll be insufferable around the house today...

Oh, I'll be insufferable around the house today...

Cooking My Way Out of a Paper Bag

Last week's New Scientist carried my article on forgotten chef Nicolas Soyer and his 1911 book Paper Bag Cookery, which launched fad that dispensed with pots and pans in favor of cooking everything in paper bags. It was well ahead of its time, as Soyer's arguments for paper bag cookery (easy cleanup, convenience, ideal for bachelors and small apartments) are exactly the same factors that drive the use of paperboard packaging for microwaveable meals today.

As it happened, my piece coincided with a spate of reviews for Ruth Cowen's Relish, a new biography of Nicolas's grandfather, the hugely influential and equally forgotten Alexis Soyer. The Guardian aptly describes Alexis as "the Victorian Bob Geldolf":

When not working alongside Florence Nightingale, the elder Soyer came up with some cracking good cookbooks -- witness these reprints in the Independent last week of his recipes for Lamb Cutlets Reform and Macaroni and Almond Croquettes With Raspberries.

As it happened, my piece coincided with a spate of reviews for Ruth Cowen's Relish, a new biography of Nicolas's grandfather, the hugely influential and equally forgotten Alexis Soyer. The Guardian aptly describes Alexis as "the Victorian Bob Geldolf":

He invented the cafetière. He fed tens of thousands with his patent soup kitchens during the Irish potato famine. He was the author of the first genuinely best-selling cookbook. He was the darling of aristocrats, politicians and the press. His face adorned Crosse & Blackwell sauce bottles. At his own expense - and with fatal consequences for his health - he travelled to the Crimea to reform the army's mess arrangements with his own design of portable cooking stove.

When not working alongside Florence Nightingale, the elder Soyer came up with some cracking good cookbooks -- witness these reprints in the Independent last week of his recipes for Lamb Cutlets Reform and Macaroni and Almond Croquettes With Raspberries.

Saturday, July 22, 2006

Hello, Harry!

To accompany my article on Harry Stephen Keeler in the latest issue of Fine Books & Collections, editor Scott Brown has assembled a kickass online Keeler bibliography.

Flip to page 48 in the new issue, and you'll also find that Scott's pulled off something that I couldn't: namely, tracking down a surviving Keeler relative! Here's Susan Sylvan on her step-uncle Harry: "[Keeler] was not what you would call a communicative person. He seemed like he was in his own world.... He was very taciturn. He may have been communicative in what he wrote, but not in person."

Sounds about right...

Flip to page 48 in the new issue, and you'll also find that Scott's pulled off something that I couldn't: namely, tracking down a surviving Keeler relative! Here's Susan Sylvan on her step-uncle Harry: "[Keeler] was not what you would call a communicative person. He seemed like he was in his own world.... He was very taciturn. He may have been communicative in what he wrote, but not in person."

Sounds about right...

The Madcap Writes

When I arrived in London last week, the talk there was not about the Folio: it was about the death of Syd Barrett. There was an extraordinary outpouring in the newspapers, all more or less repeating the same tropes -- crazy diamond, acid casualty, the lost muse of Pink Floyd who hid in his Mum's house, etc etc etc.

The problem was that none of these accounts quite added up. For one thing, pictures of him showed a rather smartly dressed old fellow, apparently content to bike to Cambridge shops for the groceries and for wood for his DIY projects:

So what exactly was going on here? Lost amid all the fuss was this astounding late-appearing article in the Times by Barrett's biographer, Tim Willis. In it, a much less sensational and more nuanced portrait emerges from an interview with his sister Rosemary:

In fact, Willis's article has not one but two surprising revelations. The first -- also mentioned in passing in this Independent obituary -- is the suspicion among those who knew him that Barrett had Asperger's Syndrome. Consider that, and his eccentric withdrawal into art -- and his utter lack of interest in fans or the press -- starts to make a lot more sense.

The second, even more astounding bit of news-- buried deep within Willis's article -- is that Syd Barrett authored an as-yet unpublished manuscript. Here's his sister again:

So if there's one that we already know of, it's only sensible to wonder: is there a cupboard full of unpublished Syd Barrett manuscripts in that Cambridge semi-detached?

The problem was that none of these accounts quite added up. For one thing, pictures of him showed a rather smartly dressed old fellow, apparently content to bike to Cambridge shops for the groceries and for wood for his DIY projects:

So what exactly was going on here? Lost amid all the fuss was this astounding late-appearing article in the Times by Barrett's biographer, Tim Willis. In it, a much less sensational and more nuanced portrait emerges from an interview with his sister Rosemary:

Barrett lived in the semi with his mother until her death in 1991 and then remained there alone. “So much of his life was boringly normal,” said Rosemary. “He looked after himself and the house and garden. He went shopping for basics on his bike — always passing the time of day with the local shopkeepers — and he went to DIY stores like B&Q for wood, which he brought home to make things for the house and garden.Rather fits better with that photo than the crazy diamond acid casualty stuff, doesn't it?

“Actually, he was a hopeless handyman, he was always laughing at his attempts, but he enjoyed it. Then there was his cooking. Like everyone who lives on their own, he sometimes found that boring but he became good at curries.... He took up photography, and sometimes we went to the seaside together. Quite often he took the train on his own to London to look at the major art collections — and he loved flowers. He made regular trips to the Botanic Gardens and to the dahlias at Anglesey Abbey, near Lode. But of course, his passion was his painting."

In fact, Willis's article has not one but two surprising revelations. The first -- also mentioned in passing in this Independent obituary -- is the suspicion among those who knew him that Barrett had Asperger's Syndrome. Consider that, and his eccentric withdrawal into art -- and his utter lack of interest in fans or the press -- starts to make a lot more sense.

The second, even more astounding bit of news-- buried deep within Willis's article -- is that Syd Barrett authored an as-yet unpublished manuscript. Here's his sister again:

"It’s not that he couldn’t apply his mind. He read very deeply about the history of art and actually wrote an unpublished book about it, which I’m too sad to read at the moment."

So if there's one that we already know of, it's only sensible to wonder: is there a cupboard full of unpublished Syd Barrett manuscripts in that Cambridge semi-detached?

In Praise of Maggs & His Many Brothers

Yes, I'm back after a month away of moving house + a research trip to London. I was over there for the Sotheby's Folio auction -- my usual misadventures at which, naturally, I will recount in my next book. Until then, the two newspaper accounts that get the closest to what it was like being there is this one in the Guardian, and today's Times of London eyewitness account. A week late and buried under an obscure headline, the latter's all too easy to miss -- but it's a valuable insider's view by Ed Maggs, of the grand old London bookselling family of Maggs Brothers.

Old Maggs Bros. catalogues, incidentally, are catnip for any serious bibliophile. I can't tell you how gutted I was when, stopping by Maggs after the auction, it turned out they didn't have any of their own old catalogues for sale. Old antiquarian catalogues are one of those brilliant resources that they never tell you about in grad school. There is an egregious disconnect between the knowledge of academic scholars and the knowledge of booksellers; scholars are in the habit of "rediscovering" works that are old news to anyone who actually works the floor.

Catalogues are not an obvious source, granted: why read old listings from seventy and eighty years ago, for books that are no longer for sale -- indeed, for copies that might have been destroyed in floods and fires years ago? Yet their descriptions are brilliantly practical guides to literature, written by people who live and breathe old books -- and whose very livelihood depends on their ability to describe them.

I've often thought that grad programs in literature should set up some internships in antiquarian shops, or in the books department of an auction house. (For that matter, those studying modern lit would do well to spend a month or two in a publishing house, the better to understand the means of production.) Had I only known to try it, a semester in Maggs or Quaritch would have been an eye-opener to me as a student.

And yet I've never heard of program doing this. Someone really should.

Old Maggs Bros. catalogues, incidentally, are catnip for any serious bibliophile. I can't tell you how gutted I was when, stopping by Maggs after the auction, it turned out they didn't have any of their own old catalogues for sale. Old antiquarian catalogues are one of those brilliant resources that they never tell you about in grad school. There is an egregious disconnect between the knowledge of academic scholars and the knowledge of booksellers; scholars are in the habit of "rediscovering" works that are old news to anyone who actually works the floor.

Catalogues are not an obvious source, granted: why read old listings from seventy and eighty years ago, for books that are no longer for sale -- indeed, for copies that might have been destroyed in floods and fires years ago? Yet their descriptions are brilliantly practical guides to literature, written by people who live and breathe old books -- and whose very livelihood depends on their ability to describe them.

I've often thought that grad programs in literature should set up some internships in antiquarian shops, or in the books department of an auction house. (For that matter, those studying modern lit would do well to spend a month or two in a publishing house, the better to understand the means of production.) Had I only known to try it, a semester in Maggs or Quaritch would have been an eye-opener to me as a student.

And yet I've never heard of program doing this. Someone really should.