Friday, January 27, 2006

Friday Stubble

I'm heading out on a redeye to London tonight, so there may or may not be any postings this weekend depending on (a) my exhaustion and (b) wi-fi access for my cranky old iBook. (I just can't part with it -- it's tangerine colored.) What there will be, though, is yours truly up to his eyeballs in Folios at the British Library.

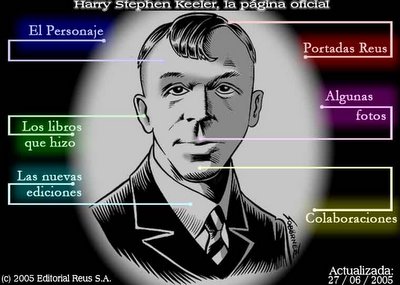

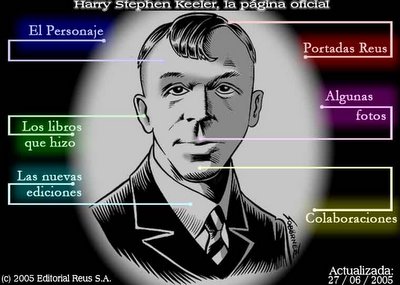

Oh, and: there's a splendid in-depth Village Voice article this week on Harry Keeler!

Oh, and: there's a splendid in-depth Village Voice article this week on Harry Keeler!

Sunday, January 22, 2006

Wordless Bookbinding

There's an entertaining profile in the Harvard Crimson of the proprieter of the Harvard Book and Binding Service:

Marshall says he decided to sell books because he didn’t want to apply for a vendor’s license. “The First Amendment was my vendor’s license,” he says. He went to the Brattle Book Shop, which adjoins the Boston Common, and talked the owner into selling him a suitcase full of 18th-century books on credit. Then he set up shop on a patch of Square pavement and sold books to passersby at lunchtime. Within a year, he had learned about rare books and how to find good ones....Also: he figured out that a stagnating mash of water, grass and cocoa powder is great for breeding bacteria. Though some of my old roomates could have told him that just from looking at our kitchen sink.

Then, browsing in Houghton Library one day, he stumbled across an 18th-century French dictionary, with an illustrated entry on bookbinding. Using the explanation, Marshall taught himself to bind books. He does not speak French.

“I couldn’t read a word of it, so I just figured it out from the pictures,” he says.

100 Spinning Plates

I've always been faintly irritated by the 6-week book review cycle at most newspapers, and so I always try to give kudos when I see someone venture outside the tiresome demand for New! New! The Latest Thing!

My old hometown paper the Portland Mercury takes the prize this week for reviewing Rob Christopher's randomized narrative card deck 100 Spinning Plates over two years after its release. It's a mixed review, but still -- if Coover's deck of cards in McSweeney's #16 floats your boat, you might want to check out this one as well....

My old hometown paper the Portland Mercury takes the prize this week for reviewing Rob Christopher's randomized narrative card deck 100 Spinning Plates over two years after its release. It's a mixed review, but still -- if Coover's deck of cards in McSweeney's #16 floats your boat, you might want to check out this one as well....

Read It and Sweep

In response to yesterday's post about odd materials in book manufacturing, a reader points out that not only did Marvel Comics writer Mark Gruenwald have his cremated ashes mixed into the ink of the first printing of his next book.... but that there's also a copy of that cremain printing for sale on eBay right now.

Saturday, January 21, 2006

National Geograph

I recently stumbled across Geograph British Isles: it's a volunteer attempt to get a photograph from every grid square (ie everywhere square kilometer) of Great Britain and Ireland.

They're already up to 28% of the country, and the photos plus their captions are often weirdly captivating. For instance, check out this one for OS Grid SH6139:

They're already up to 28% of the country, and the photos plus their captions are often weirdly captivating. For instance, check out this one for OS Grid SH6139:

Explosives Hut. One of the buildings on the old Cookes Explosives site, formerly used for preparing and packaging explosives. The grey stone wall is a blast barrier, about 10ft thick. The brick built hut has a 'floating' roof, so that any explosion would dissipate upwards, rather than outwards.

Now Pardon Me While I Mow My Bookcase

Today's Times of London reports that flecks of grass are being woven into the endpapers of "World Champions by Geoff Hurst, hero of England’s 1966 World Cup victory." The grass is taken from field sod bought from the 2001 teardown of Wembley Stadium.

I've seen attempts over the centuries by publishers to make paper with everything from hay to very thinly rolled steel. (Seriously.) Stadium grass is a new one, I'll admit. So I'll throw this open to my fellow antiquarians (respond at collinslibrary AT aol.com) : what's the oddest primary material or additive you've seen a publisher, past or present, try to manufacture a book out of?

I've seen attempts over the centuries by publishers to make paper with everything from hay to very thinly rolled steel. (Seriously.) Stadium grass is a new one, I'll admit. So I'll throw this open to my fellow antiquarians (respond at collinslibrary AT aol.com) : what's the oddest primary material or additive you've seen a publisher, past or present, try to manufacture a book out of?

Libros Locos

Glowing reviews are coming in for Harry Stephen Keeler and The Riddle of the Traveling Skull at the Chicago Reader (pdf download) and at Baltimore City Paper, who note:

As chance would have it, a Keeler revival is also underway in Spain -- his works remained in print over there years after English-language publishers gave up on him, with the odd result that some of Keeler's books were only available in Spanish. With his return to print in Spain, his publisher Editorial Reus S.A. snapped up harrystephenkeeler.com to spread the word about Señor Keeler...

Keeler’s nonsense feels as naturally immediate as talking to a stranger at a bar, the tales twice as convoluted, preposterous, and redundant, and everything 50 times more fun.... Five rereadings of the final chapters haven’t clarified a freaking thing. Which, again, hardly matters. Truly bonkers writers are one thing; a truly bonkers writer this enjoyable, prolific, and unknown is a gift from the Dada gods.

As chance would have it, a Keeler revival is also underway in Spain -- his works remained in print over there years after English-language publishers gave up on him, with the odd result that some of Keeler's books were only available in Spanish. With his return to print in Spain, his publisher Editorial Reus S.A. snapped up harrystephenkeeler.com to spread the word about Señor Keeler...

Site of the Living Dead

While some websites roll over and play dead, others still think they're alive. Over at Ghost Sites, Steve Baldwin has been looking for the oldest living website -- that is, the oldest functioning site that is still frozen in time without an update. His winner so far appears to be this website for Pinball Expo '94....

Sunday, January 15, 2006

... And Not Over Here

Just Twenty Little Pieces

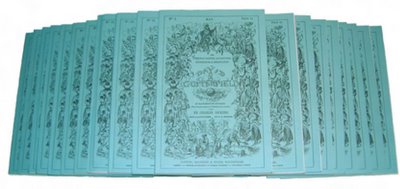

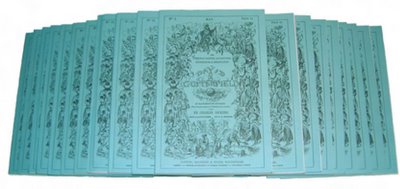

I have an article in the latest Fine Books magazine about the twenty-part David Copperfield reprint by the Charles Dickens Part-Works Project, part of a series of really beautifully made facsimile reprints of the very first original serial editions of his books. These are the 32-page paperbound monthly magazines that Dickens subscribers received hot off the press while he wrote the book. (In at least one case, a family death actually caused him to miss a month.) Typically this lasted about two years; once Dickens finished writing his book and had the last installment in subscriber mail-slots a few weeks later, readers would then take their well-thumbed magazines to a binder and have them stitched and bound as a "book."

What fascinated me in my Fine Books piece is the thing we don't see in Dickens editions anymore, but that those original readers did... namely, the ads for everything from Spermazine Wax Lights to the Invisible Ventilating Head of Hair:

The new facsimile edition costs dearly, but it's an utterly charming and actually rather helpful way to read a Victorian work. And it has probably spoiled me: I'll feel a little cheated whenever I encounter a sterilized modern edition of Dickens.

What fascinated me in my Fine Books piece is the thing we don't see in Dickens editions anymore, but that those original readers did... namely, the ads for everything from Spermazine Wax Lights to the Invisible Ventilating Head of Hair:

Page to the end of David Copperfield, past an elaborate foldout insert for Letts, Son & Steet Stationary—also purveyors of "Packing Cases for Globes. Having hitherto from their absurd costliness formed an impediment to the transmission of Globes into the Country."—and you find the mercantile poetry that once charmed away sovereigns from hardworking Englishmen. And I do mean poetry: the inside back cover of every issue of David Copperfield featured an advertisement in verse by E. Moses & Son, Tailors. The store actually retained its own poet. One such Moses production—"On An Old Picture"—reads with a strange pathos today:How that old picture brings before the eye

The Dress peculiar to days gone by!

Look at the figures! such outlandish styles

Seem'd fashioned only to provoke smiles.

How very diff'rent were the dresses worn

When that old-fashion'd picture first was drawn.

See! there's a curious coat—and there's a hat!

And there's a bonnie waistcoat! look at that!...

The poems always end with the triumphant splendiforousness of Moses & Son clothing, before then proceeding to such useful particulars as "MOURNING TO ANY EXTENT AT FIVE MINUTES NOTICE"—a claim that brings to mind a squad of tophatted Victorians sliding down a firehouse-style pole, all frantically running out to a funeral.

The new facsimile edition costs dearly, but it's an utterly charming and actually rather helpful way to read a Victorian work. And it has probably spoiled me: I'll feel a little cheated whenever I encounter a sterilized modern edition of Dickens.

Saturday, January 14, 2006

Castles in the Air

An interesting item from 1922 on eBay this week: the Chicago Tribune Tower Competition book. In the words of the seller:

A similar collection of World Trade Center proposals was published by Rizzoli in 2004. It makes me curious -- has anyone ever published a collection entirely dedicated to unrealized architectural proposals?

The Tribune Company's famous 1922 competition to design the "World's Most Beautiful Office Building" as its headquarters captured the interest of an international audience of architects, business leaders, and the public at large. The Tribune's eccentric publisher Colonel Robert McCormick offered 100,000 Dollars as prize money and entries poured in from 22 countries. The competition was one of the largest, most important and most controversial design contests of the 1920's. The 263 entries for the design of the new Tribune Tower represented a broad constellation of approaches to the skyscraper at a time of transition. The competition was won by Raymond Hood - who would later build the Rockefeller Center.... This original first edition 1923 that came out after the competition contains all the designs submitted.... with multiple artist conception plates of all the 263 submitted building[s].

A similar collection of World Trade Center proposals was published by Rizzoli in 2004. It makes me curious -- has anyone ever published a collection entirely dedicated to unrealized architectural proposals?

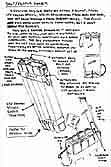

Prisoners' Inventions

The latest LA Weekly mentions a fascinating-sounding book that came out last year: Prisoners' Inventions, published by the artist collective Temporary Services and distributed by U. Chicago Press. TS describes it as:

One of the more elegant designs is a salt and pepper shaker made out of popsicle sticks:

Although Angelo has kept a low profile, there is an extensive interview with Temporary Services about the project.

A collaboration with Angelo, an incarcerated artist. He illustrated many incredible inventions made by prisoners to fill needs that the restrictive environment of the prison tries to supress. The inventions cover everything from homemade sex dolls, condoms, salt and peper shakers to chess sets. We collaborated on this project with Angelo for over two years. We had many additional collaborators who made a book, exhibition of re-created inventions and a prison cell possible.

One of the more elegant designs is a salt and pepper shaker made out of popsicle sticks:

Although Angelo has kept a low profile, there is an extensive interview with Temporary Services about the project.

Solresol Comes Alive

A fun surprise: word came this week from the NYC-based band Melomane that they have an album out called Solresol; the title song, named after a 19th century musical language, came about after one of the band members ran into my Banvard's Folly piece about it in McSweeney's. They'll be playing in midtown this Monday at the Rodeo Bar (375 3rd Ave.).

Sunday, January 08, 2006

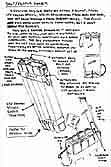

Picture This

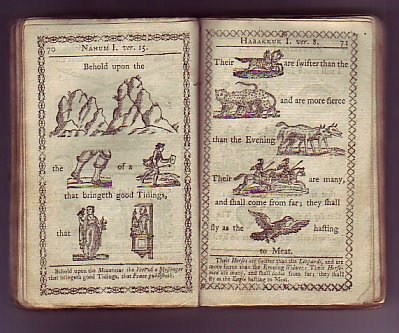

A couple of curious older items turned up for auction this week, neither of which I've seen before. First, there's currently an auction for a 1790 "Hieroglyphick Bible":

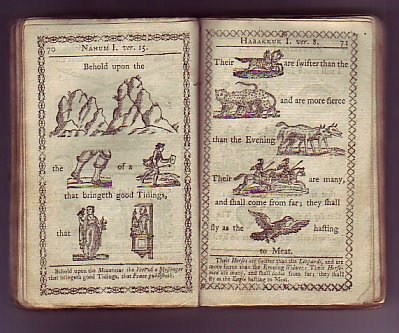

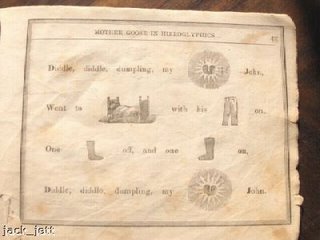

Earlier this week there was also a first edition 1849 Mother Goose in Hieroglyphics. The latter went for a hundred bucks, and could very easily have gone for even more -- children's books, for obvious reasons, are much less likely to survive over the years than grownup ones:

As you'll have already guessed, what they were calling "hieroglyphics" is what we'd call a rebus. To my surprise, I found that the Mother Goose volume actually went through a good number of printings, including a 1960s revival capped off by a facsimile Dover edition in 1972. It's out of print now, but thanks to the Dover edition they're quite cheap used.

Earlier this week there was also a first edition 1849 Mother Goose in Hieroglyphics. The latter went for a hundred bucks, and could very easily have gone for even more -- children's books, for obvious reasons, are much less likely to survive over the years than grownup ones:

As you'll have already guessed, what they were calling "hieroglyphics" is what we'd call a rebus. To my surprise, I found that the Mother Goose volume actually went through a good number of printings, including a 1960s revival capped off by a facsimile Dover edition in 1972. It's out of print now, but thanks to the Dover edition they're quite cheap used.

Literature By Numbers

Thursday's Inside Higher Ed has a great article by Scott McLemee on literary theorist Franco Moretti, author of Graphs, Maps and Trees: Abstract Models for a Literary History and the upcoming The Novel: History, Geography and Culture:

Anyway, despite the silly posturing, it sounds like there's some very interesting stuff in Moretti:

Of course, the devil will be in the details on just how he classified them, but by Moretti's account niche fiction consistently rises and then falls over the course of about one generation -- about 25 years or so. Actually, the generational comparison might be a rather apt one, as McLemee points out:

This is pretty much the argument I made in The Believer a while back about Virginius Dabney's utterly forgotten but extraordinarily ambitious novel Don Miff: there's lots of brilliant work out there, but it must be brilliance that can be adapted to our present needs -- otherwise, it goes extinct. It will not surprise any of my readers that I've always been very skeptical of the Great Man model of history, particularly when applied to something as subjective as literature. Moretti sounds like a fellow after my own heart in this regard, and I'll be first in line when his book comes out.

About two years ago, a prominent American newspaper devoted an article to Moretti’s work, announcing that he had launched a new wave of academic fashion by ignoring the content of novels and, instead, just counting them. Once, critics had practiced “close reading.” Moretti proposed what he called “distant reading.” Instead of looking at masterpieces, he and his students were preparing gigantic tables of data about how many books were published in the 19th century.... Moretti and his students have been working their way across 19th century British literature with an adding machine — tabulating shelf after shelf of Victorian novels, most of them utterly forgotten even while the Queen herself was alive.It's basically a rhetorical stunt to oppose close reading and "distant reading": there's no reason they can't co-exist. When I was taking classes by one of the best literary specialists I've ever met -- David Reynolds, who has since written on Whitman and John Brown -- he was fulsome in his praise of one study that analyzed old New York Public Library call slips to determine library reading habits from a century earlier. (The upshot, as I recall, was that despite received wisdom to the contrary, just as many men as women were reading novels back then.)

Anyway, despite the silly posturing, it sounds like there's some very interesting stuff in Moretti:

One of Moretti’s graphs shows the emergence of the market for novels in Britain, Japan, Italy, Spain, and Nigeria between about 1700 and 2000. In each case, the number of new novels produced per year grows — not at the smooth, gradual pace one might expect, but with the wild upward surge one might expect of a lab rat’s increasing interest in a liquid cocaine drip.

“Five countries, three continents, over two centuries apart,” writes Moretti, “and it’s the same pattern ... in twenty years or so, the graph leaps from five [to] ten new titles per year, which means one new novel every month or so, to one new novel per week. And at that point, the horizon of novel-reading changes.".... Then the niches emerge: The subgenres of fiction that appeal to a specific readership. On another table, Moretti shows the life-span of about four dozen varieties of fiction that scholars have identified as emerging in British fiction between 1740 and 1900.

Of course, the devil will be in the details on just how he classified them, but by Moretti's account niche fiction consistently rises and then falls over the course of about one generation -- about 25 years or so. Actually, the generational comparison might be a rather apt one, as McLemee points out:

Moretti is a cultural Darwinist, or something like one. Anyway, he is offering an alternative to what we might call the “intelligent design” model of literary history, in which various masterpieces are the almost sacramental representatives of some Higher Power. (Call that Power what you will -– individual genius, “the literary imagination,” society, Western Civilization, etc.) Instead, the works and the genres that survive are, in effect, literary mutations that possess qualities that somehow permit them to adapt to changes in the social ecosystem.

This is pretty much the argument I made in The Believer a while back about Virginius Dabney's utterly forgotten but extraordinarily ambitious novel Don Miff: there's lots of brilliant work out there, but it must be brilliance that can be adapted to our present needs -- otherwise, it goes extinct. It will not surprise any of my readers that I've always been very skeptical of the Great Man model of history, particularly when applied to something as subjective as literature. Moretti sounds like a fellow after my own heart in this regard, and I'll be first in line when his book comes out.

It's Official: British Weather Sucks

Today's Times of London review of Tom Fort's Under the Weather: Us and the Elements (available in the UK but not yet in the US) includes this amusing bit of lore:

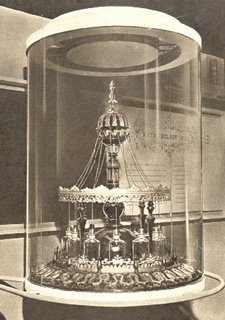

In going through 19th century issues of Notes and Queries I came across a number of letters referring to this peculiar invention, some by people who swore they saw it, and others insisting it was surely a hoax. But Merryweather's "Tempest Prognosticator" was indeed shown at the Great Exhibition of 1851:

An antique barometer dealer in Britain has apparently now built a working replica.

There are many cranks and eccentrics here, but none more interesting than Dr George Merryweather (apt name), a general practitioner in Whitby, Yorkshire, the coastal town later honoured with a visit by Count Dracula. Merryweather had read a letter from the poet William Cowper to his cousin Lady Hesketh extolling the prophetic virtues of his pet leech: “I have a leech in a bottle that foretells all these prodigies and convulsions of Nature. No change in the weather surprises him . . . he is worth all the barometers in the world.”

Drawing inspiration from Cowper’s fond report, Merryweather confined leeches in bottles and kept a close watch on their movements. When the leeches were calm, the weather was mild, but when they were restless it was in anticipation of a storm at sea. Thus was born Merryweather’s Tempest Prognosticator, a device with 12 leeches in as many bottles on a specially constructed circular stand. Tubes and a bell struck by a dozen little hammers completed the design. Fort observes wryly that Merryweather was deeply attached to his bloodsuckers.

In going through 19th century issues of Notes and Queries I came across a number of letters referring to this peculiar invention, some by people who swore they saw it, and others insisting it was surely a hoax. But Merryweather's "Tempest Prognosticator" was indeed shown at the Great Exhibition of 1851:

On the circular base of his apparatus he installed glass jars, in each of which a leech was imprisoned and attached to a fine chain that led up to a miniature belfry -- from whence the tinkling tocsin would be sounded on the approach of a tempest." The model was displayed in the Dome of Discovery's 'Sky' gallery...

An antique barometer dealer in Britain has apparently now built a working replica.

Saturday, January 07, 2006

Prodigal Son

Today's Guardian has some fascinating revelations about Native Son author Richard Wright's final novel that remains unpublished:

Island of Hallucination, begun in 1958, represented a late departure for Wright: it was the first time he had written about Paris, his home for the past 11 years. Dispatching a completed draft to his agent, Paul Reynolds, at the beginning of 1959, he sounded pessimistic about its chances: "I can readily think of a hundred reasons why Americans won't like this book. But the book is true. Everything in the book happened, but I've twisted characters so that people won't recognise them."....Despite the Wright estate's earlier fear of legal troubles over the Gibson-inspired character in the book, apparently Gibson himself thinks the book should be published -- so there may be some hope for it seeing the light of day at last.

After his death, Ellen permitted a small section to be printed in an anthology, but then withdrew the manuscript. It now sits among the Richard Wright papers at the Beinecke Library at Yale. For many years, Wright scholars were not permitted to read it. One biographer, Addison Gayle, stated in a footnote in his book, Ordeal of a Native Son, that his request to read Island of Hallucination "was denied".

Ellen Wright died last year, at 92. Not long before, a photocopy of Island of Hallucination, more than 500 pages in Wright's typescript, came into my hands, by an unexpected route: it was lent to me by Richard Gibson, whose presence in the novel is thought to have been behind its suppression.

Ben Who? ... Redux

Ok, back for another ride on my hobby-horse. I have already complained about the lack of press coverage for Leo Lemay's major new multi-volume bio The Life of Benjamin Franklin. So far the only newspaper review I'm seeing is, of all places, the Washington Times.

That's right: the Moonies are providing better history review coverage than the majors.

As it so happens, next Sunday falls right before the 300th birthday of Ben Franklin. You'd think this would be the perfect opportunity for, you know, one of those other Times to cover the book... but incredibly, there is no sign yet that anyone will be reviewing it.

That's right: the Moonies are providing better history review coverage than the majors.

As it so happens, next Sunday falls right before the 300th birthday of Ben Franklin. You'd think this would be the perfect opportunity for, you know, one of those other Times to cover the book... but incredibly, there is no sign yet that anyone will be reviewing it.

Behold! I Summon Reprints From the Vasty Deep!

After seeing my post last week about how I was not quite overwhelmed by Donald Barthelme's out-of-print children's book The Slightly Irregular Fire Engine, an editor at Overlook Press noted that actually they're reprinting it this fall.

(Err. Um.)

Good luck with that!

(Err. Um.)

Good luck with that!

Sunday, January 01, 2006

Happy New Year, Aspiring Writers!... Now Give Up.

Today's Times of London, under the headline Publishers Toss Booker Winners Into the Reject Pile, has what sounds like an awfully damning story:

Is award-winning literature automatically that timeless? I'm afraid not. A case in point: on Friday I received in the mail a long-awaited used copy of Donald Barthelme's one venture into children's books, The Slightly Irregular Fire Engine: Or The Hithering Dithering Djinn. As it so happens, it too was published in 1971. And also, rather conveniently, it too won a major award: in this case, the National Book Award in 1972.

Would this book be neglected today? I can answer that with complete certainty, friend: it is neglected today. It's been out of print for decades. And I will admit that when I first came across a reference to this title, I was pretty excited: A NBA winner! By Barthelme! And forgotten! Hoo boy, this is going to be a great find!

It was not a great find.

In fact, in wasn't even very good. Barthelme did a bunch of these whimsical collage jobs with Victorian public domain images in the New Yorker back in the 60's -- if you have the New Yorker CD set (and you should), you can check them out in there. This vein of his work was ok for what it was, but it hasn't aged well, in part because even when it came out it wasn't particularly visually sophisticated. Three years earlier Terry Gilliam was doing this stuff better -- and animating it.

The upshot: I could have written that Times piece, with almost the same headline, and made it sound just as damning by sending around a NBA winner. Because if you submitted The Slightly Irregular Fire Engine to 21 agents and editors today, it wouldn't get accepted anywhere either. And it wouldn't have gotten accepted for good reason. For starters, it's not 1971 anymore.

The ridiculous thing is that this Times piece could have been done well, had they simply bothered to use a more recent work. But that leaves open a question: would a well-regarded new work have been so universally rejected? (The cynical journalist in me also wonders: Did they try this stunt with a newer work first and find that they didn't have a good enough story?)

Listen, I'm all for my fellow hacks short-sheeting agents and and giving wedgies to editors: you'd need to be a writer without a pulse to not get a certain adolescent gratification from it. And it can be done well. Some of you might recall that back in 1998, a writer for the late and lamented smartasses at Suck.com (no direct link, because the domain's owned by a pornster now) pulled a splendid joke on the New Yorker. After getting a piece rejected by its Shouts & Murmurs section, he resubmitted the exact same piece under a fake "Bruce McCall" address. The result was exactly what you'd expect:

To be fair, that wasn't the only difference. The agent, after all, had also pitched it to them over lunch. But it was exactly the same writing sample.

So what does all this tell us? That publishers like work that looks current? That they are much more likely to trust a friend or acquaintance than a complete stranger? The latter's a little dispiriting, perhaps. But the extent to which this surprises you depends on how much you think publishing differs from every other known business since the beginning of time.

I'm not sure if that constitutes a malaise.

Publishers and agents have rejected two Booker prize-winning novels submitted as works by aspiring authors. One of the books considered unworthy by the publishing industry was by V S Naipaul, one of Britain's greatest living writers, who won the Nobel prize for literature. The exercise by The Sunday Times draws attention to concerns that the industry has become incapable of spotting genuine literary talent.I say it sounds awfully damning. But look carefully at what they sent. Naipaul's novel was published in 1971. What was an agent supposed to think of the originality and freshness of ostensibly new writing that was, in fact, probably at the proofreader when the Beatles were still playing on a London rooftop?

Typed manuscripts of the opening chapters of Naipaul's In a Free State and a second novel, Holiday, by Stanley Middleton, were sent to 20 publishers and agents. None appears to have recognised them as Booker prizewinners from the 1970s that were lauded as British novel writing at its best. Of the 21 replies, all but one were rejections.

Is award-winning literature automatically that timeless? I'm afraid not. A case in point: on Friday I received in the mail a long-awaited used copy of Donald Barthelme's one venture into children's books, The Slightly Irregular Fire Engine: Or The Hithering Dithering Djinn. As it so happens, it too was published in 1971. And also, rather conveniently, it too won a major award: in this case, the National Book Award in 1972.

Would this book be neglected today? I can answer that with complete certainty, friend: it is neglected today. It's been out of print for decades. And I will admit that when I first came across a reference to this title, I was pretty excited: A NBA winner! By Barthelme! And forgotten! Hoo boy, this is going to be a great find!

It was not a great find.

In fact, in wasn't even very good. Barthelme did a bunch of these whimsical collage jobs with Victorian public domain images in the New Yorker back in the 60's -- if you have the New Yorker CD set (and you should), you can check them out in there. This vein of his work was ok for what it was, but it hasn't aged well, in part because even when it came out it wasn't particularly visually sophisticated. Three years earlier Terry Gilliam was doing this stuff better -- and animating it.

The upshot: I could have written that Times piece, with almost the same headline, and made it sound just as damning by sending around a NBA winner. Because if you submitted The Slightly Irregular Fire Engine to 21 agents and editors today, it wouldn't get accepted anywhere either. And it wouldn't have gotten accepted for good reason. For starters, it's not 1971 anymore.

The ridiculous thing is that this Times piece could have been done well, had they simply bothered to use a more recent work. But that leaves open a question: would a well-regarded new work have been so universally rejected? (The cynical journalist in me also wonders: Did they try this stunt with a newer work first and find that they didn't have a good enough story?)

Listen, I'm all for my fellow hacks short-sheeting agents and and giving wedgies to editors: you'd need to be a writer without a pulse to not get a certain adolescent gratification from it. And it can be done well. Some of you might recall that back in 1998, a writer for the late and lamented smartasses at Suck.com (no direct link, because the domain's owned by a pornster now) pulled a splendid joke on the New Yorker. After getting a piece rejected by its Shouts & Murmurs section, he resubmitted the exact same piece under a fake "Bruce McCall" address. The result was exactly what you'd expect:

We can now close the book on everyone's worst suspicion about the New York publishing scene: It's the byline, stupid. When the piece was sent to The New Yorker's clunky new email system under the alias bruce_mccall@cheerful.com, it received not the usual terse and tardy thanks-but-no-thanks but a speedy, gushing acceptance from Shouts and Murmurs editor Susan Morrison. (An invitation to lunch with Steve Martin only served to gild the lily.)I'm no stranger to this phenomena myself. Last year in the Village Voice I wrote about the bizarre experience of getting simultaneously accepted and rejected on the same day in 1999:

Years ago, back when I'd never sold a word, my new agent called me one morning with great news -- an editor at a certain large Manhattan publishing house was intrigued by the book I was working on. Yes! I thought. Success at last!

Mere hours later, a thick manila envelope thudded through the mail slot of my San Francisco flat. And, lo, the return address was for this very same publisher. My, they were eager. Impressed by their lightning speed, I tore it open and pulled out a sheaf of battered papers. It took a moment until I realized that I was looking at the proposal for my own book -- only, in an extraordinary coincidence, it was one I had sent into their slush pile, un-agented and unsolicited, a full 18 months earlier. This proposal was accompanied by a brief but stunning handwritten note from their submissions reader: She could not ever see my book being published. Not by them -- and not, for that matter, by anyone else.

I stood in my hallway, dazed with disbelief. I'd never gotten anything other than photocopied rejection slips before. But here's what was really strange: This proposal was identical to the one that their acquisitions editor, unknown to the lowly submissions reader, was now praising. The only difference was an agent's cover sheet.

To be fair, that wasn't the only difference. The agent, after all, had also pitched it to them over lunch. But it was exactly the same writing sample.

So what does all this tell us? That publishers like work that looks current? That they are much more likely to trust a friend or acquaintance than a complete stranger? The latter's a little dispiriting, perhaps. But the extent to which this surprises you depends on how much you think publishing differs from every other known business since the beginning of time.

I'm not sure if that constitutes a malaise.